New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

“If he starts to slide, jump into that crevasse,” says Dan. The counterweight would be the best way to keep us all from skidding into the next slit below.

I look down into a bottomless hole, blue and terrifying. For a second, or maybe even two, I imagine drinking coffee, a cat on my lap, running shoes waiting on the doormat. I would give anything to be there. To be any place other than tied between two guys on a melting glacier.

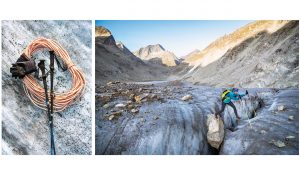

I want off this nerve-racking glacier, the last before our final destination of Zermatt, but the only way off is to keep moving, not to have a melt down. We are weaving our way through the seemingly endless maze ahead of us, navigating the least risk, backtracking. I stamp my crampons harder into the ice, ready to dive onto my ice axe or even jump into that abyss as Pascal inches his way forward, probing the snow bridge ahead of him.

“This is not good,” I hear him mutter to himself as he scans the crevasses to piece together our path.

Just a few weeks earlier, on a run with Dan,</strong> we had looked up at the Arolla glacier, as he pointed to a line across the ice, recalling memories of multiple trips skiing and hiking the famous Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt. Dan excitedly interrupted his own story with this question: “What if we run it?”

I knew before he finished the sentence that we would. So many adventures begin this way: a “what if” grows excitedly into a plan, and pretty soon you’re roped up to two friends on a glacier in the Alps.

Summer Skiing to Summer Running

But rather than the classic summer hiking Haute Route, which can take up to two weeks to trek, we’re travelling the Glacier Haute Route—a more direct line through the French and Swiss Alps. It stays higher without huge ups and downs into the valleys, following much of the Haute Route ski itinerary. Originally known as the summer “High Level Route,” the 55-mile journey can be hiked in six days. It moves frequently over glaciers (30 to 40 percent of the route), crosses many high passes and allows us to overnight in mountain huts. As for the ski route, a solid knowledge of the Alps, weather and how to travel on glaciers is necessary. Due to crevasses, it’s a serious route in good weather, potentially deadly in bad. An itinerary full of “what ifs.”

As a trail runner, I want to go higher, tackle more technical terrain, even trespass into spaces reserved for mountaineers. Many mountaineers, too, are moving faster and lighter, even trading burly alpine boots for the easy mobility of running shoes. The distinctions between mountain athletes are blending, as we start taking only the essentials.

My partners have more high-mountain experience, and I rely on their knowledge to learn the skills required to undertake a run like this. They both know the route, have hiked it before in summer and skied it in winter. Pascal Egli, 30, of Leysin, is one of Switzerland’s top skyrunners, a ski mountaineer and PhD student in glaciology. Dan Patitucci, of Interlaken, Switzerland, has decades of alpine experience from climbing, skiing and running. They both know how to read the terrain, assess the risks and make safe decisions. They are the right people to have knotted to either end of my rope.

In August 2017, we are taking advantage of a window of good weather. We know the glaciers will be in poor condition after a dry winter and a hot summer, so if we want to do this tour, it’s the time to go.

Leaving Le Tour in the narrow Chamonix valley,</strong> I feel the weight of my pack as we start up the steep forested switchbacks to Albert Premier Hut in our headlamps. We carry only what we need: enough warm clothing and equipment for glacier safety, crampons, ice axe and a Petzl RAD System (an ultralight crevasse-rescue system). It isn’t much, but heavier than what you’d carry on a typical running day. With the extra weight, the starting pace feels fast for me. Dan and Pascal run ahead. I start to worry I’ll drag behind the entire time, but at least on the glaciers we’ll be tied together.

The trail disappears

Soon after the hut, the trail disappears, and we rope up to cross the Glacier du Tour. I’d run to the edge of the icefield many times, but always returned by the same trail I’d come up. Today, I step onto the ice for the first time to continue beyond the trail. For better or worse, we’re bound within 20 feet of each other as we step over gaping holes on the way to Col du Tour.

We soon meet the first real challenge posed by the receding glaciers—the col we planned to climb is dry, littered with fallen rock and impassible. We are forced to re-route and climb up to another col, where we find a fixed rope to abseil down to the Plateau du Trient.

Once we’re off the rope, and back on the glacier, a few boulders fly past us. We don’t dally, and haul down the ice, quickly moving away from the rockfall and into the sea of grey ice split with gaping black crevasses. Dan and Pascal recognize the change in the level of the glacier.

“I’m shocked,” says Dan. “The plateau is usually covered in enough snow that you just walk across it.”

Today we must zigzag our way over the broken surface.</strong> Finally off the glaciers, we run down a trail into Champex. We planned to continue to Chanrion Hut to spend our first night, but the conditions have been worse than expected and the weather is shifting. We wonder whether we should continue at all. The crevasses are enough of a challenge without adding rain and poor visibility. We sit by Champex Lac, check weather forecasts, call friends and guides who might have tips on the condition of the glaciers ahead. They all say the same. “The glaciers are in bad shape,” and “It’s not good, but some people are going.”

We’re close to calling it off

but decide it’s worth a look for ourselves. When we reach the Chanrion Hut, after an easy uphill trail run, the hut keeper confirms: “The glaciers are shit.”

The next day will be big. From Chanrion, over Glacier d’Otemma, Glacier d’Arolla, Haut Glacier d’Arolla, Glacier de Bertol and finally a steep climb up to Cabane de Bertol—for a total of 16 rugged miles.

In the morning shade, we cross the Otemma Glacier, before the sun is high enough to reach us. We stop to visit the glacier-measuring station that Pascal helped install and now monitors. This enormous glacier, almost five miles long and 850 feet at its thickest, is melting at an alarming rate of four inches per day in the summer. On average, glaciers in the Alps are losing 13 feet annually. By 2050 most small glaciers will be gone and the remaining glaciers will be insignificant. By 2100 even the largest glaciers like the Aletsch, the Alps’ longest glacier at 14 miles, will barely exist, only their highest parts remaining.

“In the future, I may prefer to only travel the glaciers in winter,” says Pascal. “They’re getting dangerous and ugly.”

Before continuing up the grit-covered ice ramp</strong>, we stop briefly to stare down into a gaping moulin, a beautiful blue unknown. We move efficiently, but it’s running the trail sections between crossings that cuts the most time off our journey. Trekkers seem surprised, even concerned with our small packs and lack of ankle support as we skim across the rocky trails.

“Nice shoes,” a guide mocks after us at one point, more than a hint of disapproval in his tone.

We pass his group and a few others before reaching the next hut. Our speed doesn’t give us false confidence or security, but allows us to move away from danger and to spend less time in deteriorating conditions. We are a strong team, fit, experienced, multi-faceted, cautious; we know and trust each other. We aren’t a group of strangers tied behind a single guide depending completely on one person, and accept that it comes down to personal responsibility, knowing our own abilities and limits and making smart decisions to minimize risk.

As we discuss our plan for the final day, Bertol to Zermatt, hiking tours arrive at the hut and bulky boots fill the shelves around our running shoes.

In the early morning, we descend the ladders</strong> from our bunks and then the ladders from the Bertol hut to the glacier’s surface. We start running between the contrast of a black sky and white ground—both full of holes. Stars illuminate silhouettes of mountains, headlamps from climbers light the way up Dent Blanche and an increasing glow fills the sky. We climb to Tête Blanche over Glacier du Mont Miné in time to see sunrise on the Matterhorn.

This is the first time I see the iconic summit, but the mountain’s not the famous Toblerone chocolate shape from this angle. It stretches out of the glacier below and into the pale sky, one of the first to reach the morning sun. The view stops us for a moment, but we have to keep moving towards Zermatt. It is already warm as we make our way over the Stockjigletscher, the final glacier traverse.

“It might be the last day the route is passable,” a guide who had come from the other direction mentioned the night before, and even his tracks have melted by the following morning. We move carefully, jumping over narrow crevasses, and zigzagging our way through the puzzle with more “what ifs” intruding our thoughts.

We step off the ice with huge relief, remove our crampons and harnesses and coil the rope. Rocky moraine and sublime trail lead the final 12 miles to Zermatt. A contrast to the last hours maneuvering over the ice, heat and dust rise up from the crevasse-free trail. We speed along like finishing any other run, but with a greater relief, gratitude and a swelling of accomplishment. We’ve traveled through an environment that’s enormous and powerful and fading. I’d call it a true adventure, an epic even, and a glimpse at something bigger that leaves me asking, “Where else can running shoes take me?”