A couple of years ago my oldest sister Ellen passed away. I know that sounds blunt, but that’s how death rolls; no one ever goes like they do on Shakespearean stage. We just give up the ghost, done, a breath in and a breath out and… Together my whole family and I let her go, holding her weak hands, and then we cried and walked out of the room in the Intensive Care Unit, one less.

Along with my folks and siblings, her son, and all the extended kin, we grieved, each in our own way and yet all following a cycle of emotions as well known as back roads to nowhere. I hung in disbelief, and then I cried some more, became angry, and finally… just let it go. In waves I worked through it all, often alone. She had been such a force, and then she just seemed to give up; I blamed her for not trying hard enough to curb her impulses, and I was frustrated by the fact that she had chosen a lifestyle over her grandchildren’s need to have such a cool older lady in their lives. But that’s not how these things work, and I let her go.

The ICU doctor, a gentle and kind and empathetic young man, simply said to us, “It’s really about what quality of life she would want now.” My sister was a powerhouse of song and story, a fiendishly good cook and treasure house of knowledge about the world and all the thousands of books she had read. She loved to dance in a way that made other people move out of the way and had a laugh that was so authentic that it shone into any dark corner of any depressed room. She shone fiercely; despite all the wrong choices she may have made, she loved people and she relished in every morsel of life’s eccentricities. All of these made our decision unfortunately easy to make. We together let her go.

A year later, just before what would have been her birthday, on one of those bright February days that seems to reflect the whole of the icy world under a too blue sky, I sat down in front of the department head at the university where I had been teaching for the past 12 years. This was a mundane event–every spring we got together and she outlined the courses available and asked me which ones I’d like. Sometimes we drank tea and I always left knowing what I’d be teaching in the coming fall. It was a very reassuring day, especially given the precarious nature of my position as a part-time faculty member and the extremely low employment rate in the have-not Canadian province that I live in and love. She put her hands on her lap, entwined her fingers and, without missing a beat, said, “So, classes this coming year… there are none.”

I let it sink in: there are none. She then said something about low enrollment at the university and reduced numbers of course sections and finances and budgets and I nodded and blankly agreed that it was certainly not her fault. Like blaming the bank teller for high interest rates. Sign of the times. Maybe next year and you never know though and, yes, there were definitely other opportunities for me given my years of experience.

Twelve years, to be exact.

The next few weeks were a cycle of grief I had already known well and I rolled through them, allowing the anger to well and subside, trying to let go of the need to understand it, doing everything I could to not lay blame or feel like a failure. Like having made choices for the right reasons hadn’t landed me in nothing short of a hot mess. Mortgage, family, all of it; such mounting uncertainty really only left one choice–let it go.

The summer came and with it the reality of my unemployment. I let it go, let it sink in, let it be what it was. Despite everything, I’m still a fairly optimistic Stoic. Here was a situation that I could control to a degree, and not to another; as such, forget what I couldn’t effect and effect with vigour what I could. So, I took my old pickup, nailed the shingle to the virtual walls of social media, and started shoveling dirt, hauling mulch, pruning trees, and mowing lawns. Food still needs to land on the table and, strangely enough, bills don’t pay themselves, and kids need nourishment of body and soul. I ran through the woods when I could and rode my bike to feel free and sort my thoughts and all the while rolled through the cycles of grief that started to feel like home. An ugly, old, and cold home.

Novelist and business man Eliyahu Goldratt once said that “good luck is when opportunity meets preparation, while bad luck is when lack of preparation meets reality;” trail running and long-distance cycling have taught me these lessons a thousand times, so I have no idea why I didn’t take it more seriously. And yet, though I was entirely focussed on making ends meet, while working I often chucked safety to the side. In my mind’s eye, I can see me standing on the bed of the truck, a particularly large tree trunk perched precariously on my shoulder; I bend my knees and heave forward, pushing the trunk off, it arches up and then bounces off of the tailgate, swings back up and the butt strikes me powerfully on the side of the knee. It is the kind of pain that sinks, my legs buckle and with no more of a sound than a gasp I collapse on the pile of brush in the back of the truck. I stay there wordlessly and motionless for a few minutes; the adrenaline fades and the pain settles in. Slowly I stand and lower myself off the bed. I can hardly walk. I knew inside my bones that this was bad; I’ve broken and strained and snapped enough things to know what a wicked injury feels like, and this was a giant. I had been struck down by a giant named foolishness.

Twelve months pass. Allow me to to make what is a very long and drawn out and ultimately insanely boring story very short and sharp: I refused to listen to my body, kept running, raced a bit, ignored the pain, let it get worse, only listened to opinions that were in keeping with my desire to relentlessly progress in the only way I felt was forward and saw a minor problem become a major problem become a debilitating injury. I was forced to stop running and medical intervention has ended with me on a cold, hard, steel table getting a digital picture taken this coming week which will help to confirm several opinions that these Baker cysts and paralyzing pains in my knees are the result of posterior horn torn menisci. Serious shit.

Twelve months pass; running becomes impossible. I try to take up hiking but even the impact of that is too much and anything over an hour and I am essentially lame for days afterward. I take months off at a time, sometimes trying a run here and there, rejoicing in the freedom of it, and then suffering sitting, walking, and laying down afterward. I try a walk-to-run approach—same thing. I hammer out a 10k and figure I’m fine—sign up for an ultramarathon that night in my elation, wake up the next morning hardly able to move, and write to the race director to ask for a refund, explaining my foolishness, utterly embarrassed. My real friends reprimand me. I suffer. I wrestle with my identity and berate myself for such indulgence. I look to let go; I practice yoga, ski in the winter, and sit on the bike trainer to sweat and think. When the spring comes I ride outside. Hard. I am having a hard time finding friends as noble as trail runners though. I like traveling far on my bike; I dislike not knowing how to repair it. At one point my wife is talking to an acquaintance of hers and my name comes up; “Oh yeah, the cyclist, right?” Maybe it was never about the running, maybe it’s still just about adventure. Maybe it’s about making sure you don’t just sit around. Maybe it’s about making damn sure you don’t treat life like a Netflix original. I love my bike, love the freedom it affords. I grow to feel a new kind of belonging and just let the pains of growing a new identity ripple through me.

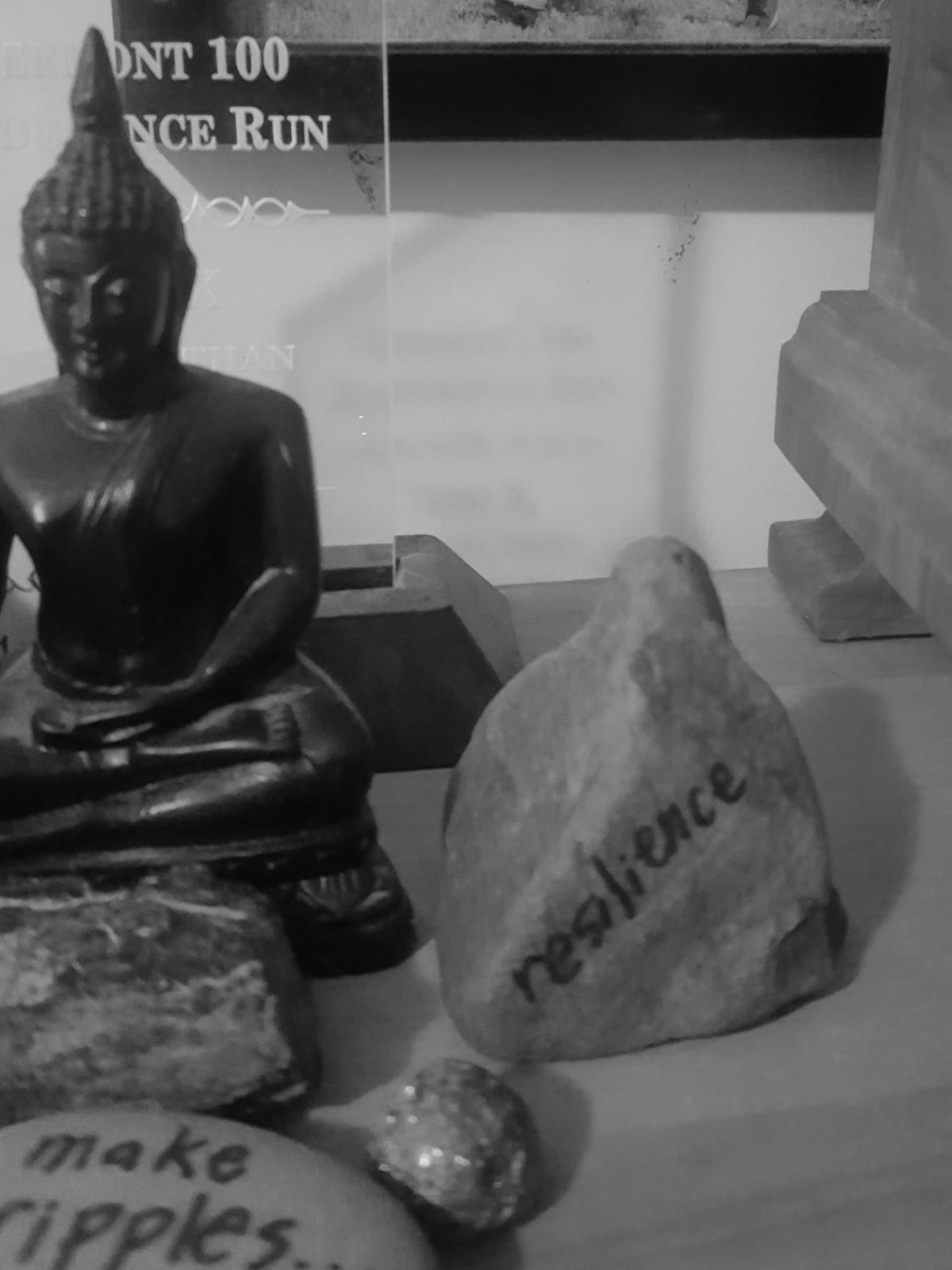

Twelve months pass; I’ve decided, at 47 years old, to go back to school and get an education degree as there seems little reason to start over. Besides, I love to teach, love the kids and ideas and books and talking. It’s really, really hard; I’m also a father of three and much older than my classmates. I don’t party. I go to bed early and I ride my bike in every spare moment I have. The course work is immense and the practicum nearly kills me. I go far past exhaustion and keep going; it is an ultramarathon of will. On the last day a teacher of ours asks us to go outside and get a stone we like from the rock garden surrounding the staircase of the building we’ve been banging away in for a solid year. When we get back in she hands out markers and tells us to write down the one thing that we take away from this degree that we’ve learned about ourselves. I uncap the pen and without hesitation write “resilience.”

Running taught me resilience. It taught me how to overcome adversity and continue when everything, including my own reason and common sense, told me to stop. Running taught me that I can count on myself. And, in a moment of utter irony, when I needed running the most, during the most stressful period of my life, it wasn’t there for me—but the resilience it taught me remained. It’s all I needed. Running taught me resilience and with it I forged a new self in the crucible of cycling.

It’s one of those unspoken things that lots of us believe—that people and books and all kinds of things come into your life when you need them. That’s some pretty cool cosmic weirdness that we all like. The flip side, though, is that they leave too; and what are we going to do with that? Are we going to be cool with that too? A book ending is one thing, a person splitting or dying is something else. And what if you have to let go of some intangible thing? What if you can’t run anymore, after it’s given you so much—health, friends, goals, maybe even some notoriety and a ton of meaning—then what? Stolen bikes can be replaced, but what if your knees just simply say, “Sorry Central Gov’ner, we just can’t give’r anymore.” Can you keep in mind, like a friend or sister that has passed, its essence? Can you suss out what mattered most and then pour that into something new? There’s no need to start over, you know.

Like teaching in the university, I’ve had to let running go. It’s time to ride my bike—in the woods, down country roads, in the basement, when I can, and sometimes all day long. Because it was never about running. At its source it’s about adventure and exploration and doing awesome things, and in the end it’s about resilience. To mourn that loss longer than needs be would be to do it a great disrespect.

So here’s to all you cool runners. I salute you. And maybe I’ll see you from the flip side of the aid station or maybe I’ll be sweeping the course on my mountain bike. But it’s okay. Let it go, all the love is still there. All of the love is just surfing the ebbs and rollers of life however you can. And that’s the real relentless forward progress.

And my sister? Yeah, she never learned to ride a bike, but loved their form and simplicity and art. Directly in front of where my trainer sits hangs a big painting she used to own of a woman riding a penny-farthing. When I inherited it I took a pen a wrote on the frame, “Ride for Ellen.” Just keep moving, everyone. It’s the only surefire way to stay positive and feed the positive wolf that I know. Ride for Ellen.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- Where in life have you learned to be resilient? And to what other parts of life and running have you been able to use that skill?

- Can you share your thoughts about this notion of “feeding the positive wolf” and actively letting go of the negative parts of life?

Resilience. All photos: Andrew Titus