[Editor’s Note: This article was written by the Trail Sisters’ Pam Smith.]

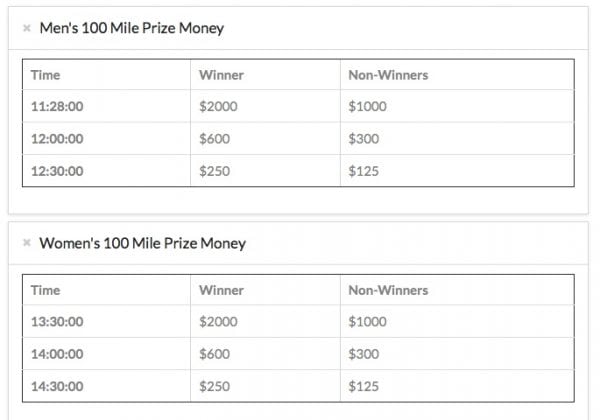

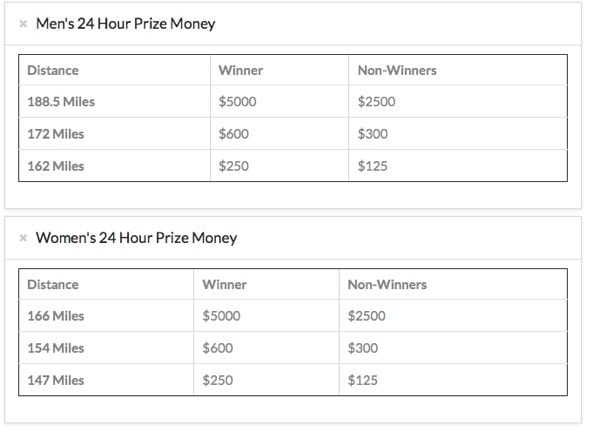

On December 10, 2016, Gina Slaby broke the 100-mile world record with a blistering time of 13:45:49 at the Desert Solstice Track Invitational, breaking Ann Trason’s world record of 13:47:41 set way back in 1991. For her efforts, the race organization awarded her $600. Had she been a man breaking the world record at Desert Solstice she would have been awarded $2,000. You see, Desert Solstice’s prize-money schedule was set so that a man breaking the 100-mile world record earns $2,000 and a man breaking the 24-hour world record earns $5,000. But for a woman to achieve the same level of pay she would’ve had to break the 100-mile record by 17 minutes and the 24-hour world record by a whopping seven-plus miles! [Update, February 27: On Facebook, Gina announced that Aravaipa Running (the race administration for Desert Solstice) was awarding her the remaining $1,400 that represented her award discrepancy, and that she was ultimately going to be paid out identically as a man setting a 100-mile world record.]

When I spoke to Gina about this she was very gracious about the whole thing, saying that she thought the discrepancy was “strange,” but that she “didn’t expect to win anything, so she was happy with the $600.”

Jamil Coury, RD of Desert Solstice and Head of Aravaipa Running had this to say when I asked him about the issue:

The original reason there was a difference in prize money for Desert Solstice was first due to Yiannis Kouros’s men’s 24-hour world record being so far above the second best performance. We had wanted to throw up a much larger amount of prize money if someone was able to break that performance. There was also a significant gap in the men’s 100-mile performance (until Zach Bitter started running track races).

Our intention was not to have a discrepancy between men’s and women’s prize money for records there, but I can see how that’s what ended up happening. All of the prize money given at our other events (Kendall Mountain Run, Flagstaff Sky Race, and Crown King Scramble) have always been equal for men and women. We even for a couple of years were offering twice as much women’s course record money for the Crown King Scramble 50K to any woman besting Ann Trason’s time there since it was so far and above any other woman’s performance. We’ve since equalized those amounts.

There is some merit to the idea that women have more potential for improving ultrarunning records then men. In a great 2013 blog post from Ian Sharman, he notes that in sprints the men’s and women’s world records differ by 10.31%, that mid-distance world records differ by 11.55%, long-distance (5k to the marathon) records differ by about 12%, yet in ultras, records for women are on average 14.66% slower than men’s. It is notable that the percentage difference increases as the distance increases, and if one were to focus on the current super-long ultra-distance records (using 100-mile, 24-hour, 48-hour, and Spartathlon records) the average is right at 17% difference, suggesting that there might not be an entirely linear comparison between men’s and women’s records at different distances. However, one conclusion is that women have more potential for improving current records.

But to me the idea of expecting someone (or a group) to jump to their expected potential without taking into account where they currently are is like a coach asking his previously sedentary new client to run 10 miles at eight minute-mile pace on his first day; for a teacher to assign a book report on Anna Karenina to a third grader; or a beginning piano class to tackle a Mozart piece, all because they believe they have the potential to do those things. Progress is made in small steps and for the most part records are improved incrementally, as well.

While women’s records may have more room for improvement, so, too, does a five year old than an eight year old. But any parent would tell you that it would be ridiculous to compare a five year old to an eight year old, as the development in that window is immense. Likewise, men’s running has had a lot longer to ‘mature’ than women’s running and so it doesn’t seem unreasonable that men’s records are ahead of women’s at this juncture. And while there may be more room for improvement, implying that a 25-year-old world record set by the greatest female ultrarunner of all time, Ann Trason, is ‘weak’ seems a bit foolish to me!

In discussions of sex equality, it is important to acknowledge that the phrase itself is a bit of a misnomer as what is generally meant is ‘equitable’ treatment of the sexes, rather than things being truly equal. Implying that men and women should be held to the same standards, especially in physical efforts, is to me a form of sexism in itself, because what it really means is that women are being expected to measure up to men’s standards. A good example of this was when the Indiana Trail 100 Mile initially offered $25,000 to anybody who broke Ian Sharman’s North American trail record of 12:44:33. Women were eligible for the prize, too… but only if they broke 12:44:33. (They subsequently changed their position after public outcry and offered the same money for a woman breaking Jenn Shelton’s (at-the-time) 100-mile trail record. No one succeeded in breaking either record and the race no longer has this incentive).

One example of equitable but unequal is the division of the prize purse at the TransRockies Run stage race. Part of their formula factors in the number of participants in each category as a surrogate for the ‘competitiveness’ in each field, with more money going to the groups with the biggest fields. While field size may not be a direct corollary to competitiveness (does a lot more slow runners make a race more competitive?), the TransRockies Run prize structure seems like a reasonable–and transparent–way to distribute different values amongst groups without a built-in bias against any one particular group.

Rarely cases do pop up where women are the benefactors of prize-money discrepancies. Last year at the Tamalpa Headlands 50k, which served as the USATF 50k Trail National Championships, $2,000 was offered for a new female course record, but only $1,000 for a new men’s course record. The prize money was donated and this was a stipulation of the donation. The donor noted a long history of inequality of sports, the desire to see a very competitive women’s field at a national-championship event, and the decade-old women’s course record (as opposed to two new course records in three years on the men’s side) as reasons for the unequal split. Race Directors Tim and Diana Fitzpatrick said they did consider how people may view the prize discrepancies, but that they felt that they could justify the decision and really wanted to promote women in ultrarunning. They note that the incentive was successful in that the race drew a very competitive women’s field and two of the ladies did go under the old course record. They also note that the men did still benefit as the prize doubled from the race’s standard $500 prize and the men’s field was also quite competitive. Tim points out that the money was donated and did not affect their operating budget or the race-entry fees. The Fitzpatricks said there were only a handful of complaints and generally the decision was well received, but they are returning to the standard (and equal) $500 prizes this year.

While I am not trying to suggest that women should get more prize money than men, I think the Tamalpa Headlands race is a great example of women raising the bar when there is good monetary incentive. If we want to see women’s records lowered we need to accept them for where they are currently and not make assumptions about where we think they should be. In 2012, Ellie Greenwood finished Western States 45 minutes under the existing course record. But did that make the efforts of Ann Trason and other past female champions less impressive because they were so far off the course-record potential? I think not! Gina broke the world record as it stood and I believe she deserved the same reward a man would have gotten for the same feat.

And while Gina might have been short changed, the story does have a bit of a happy ending. Jamil added to his comments, “After some more consideration we feel that having a difference in prize money for men’s and women’s performances at Desert Solstice isn’t our intention so we will be equalizing the amount of prize money for equal records for 2017.” I believe runners head to Desert Solstice because Aravaipa running puts on a top notch event for runners pursuing records, but it is nice to know that men and women setting those records will now be treated equally.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

- What do you think about the concept of prize-money or award-structure equality among men and women?

- How much does the award structure of a race affect its competitiveness? As in, do you think big prize money helps increase a race’s competitiveness? And how do you see this concept applying to the support of the growth of women’s trail and ultrarunning?